People | Passion | Priory

sustainability

Part of our application to the National Lottery Heritage Fund (NLHF) was to:

Transform the pace of our work to address our environmental footprint and future sustainability. We will develop a full sustainability audit and strategy and then, in the delivery stage, invest in the implementation of initiatives to transform our aging and inefficient systems and our overall performance.

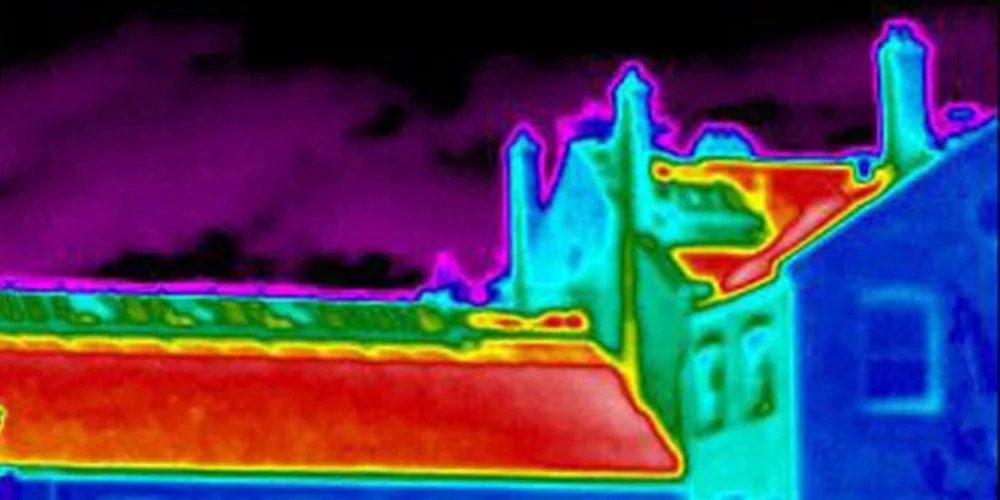

This audit, which deliberately set no restrictions or parameters, was carried out by Qoda Consulting, a specialist building services team that specialise in sustainable building methods. Its remit was to calculate our current carbon footprint and appraise the technology available to reduce this as part of the project. The report can be read here. The current total carbon footprint for the Cathedral is calculated at around 148 tonnes of CO2 per year. The space heating is the single largest contributor to this number.

The findings were that our environmental footprint, as expected for a medieval building, was high but that technology is available to mitigate our emissions. However, and this is important to recognise when reading the document, no analysis was carried out as to cost effectiveness, whether the proposals would be allowed by the planning authorities on a Grade 1 listed building in a conservation area of a National Park, or whether the proposals could be accommodated by the Cathedral and its setting. These are aspects we are exploring, both with Qoda and other consultants.

There are many recommendations we can carry out immediately, such as draught-proofing, insulation in roofs where a cavity is available, and providing lobbies to the west door and we will do this. Qoda also recommended we look at our existing boilers and upgrade these to more efficient models when they become obsolete. Incorporating more advanced technology is going to be much more challenging. To this end, Qoda recommended we look at the following:

Ground-Source Heat Pumps

These provide low-temperature water to serve a heating system that has a high surface area, such as underfloor heating. They can work with radiators but are much less efficient. At the Cathedral, we simply do not have the funds to lift the floor and install underfloor heating. Moreover, due to the ground outside the Cathedral being a former priory, we would potentially be putting at risk years of archaeology by digging the trenches that would need to contain the hundreds of metres of pipe for the heat pump to operate. Coupled with the expense of procuring the plant required, this is not a practical option at present.

Air-Source Heat Pumps

The same comments apply with regard to an air-source system working best with underfloor heating. Whilst extensive ground excavation is not required, there will need to be units placed outside the Cathedral compressing the heat captured (sample units are shown above). These units could not be hidden as they need access to the air and would be an intrusive additional to the external fabric, likely to cause problems with the planning authority. Moreover, intrusions into the medieval wall would potentially be required for pipe runs. The units can also be very noisy, which would encroach on the ambience of the Cathedral and grounds. Coupled with the expense of procuring the plant required, this is not a practical option at present.

Solar PV Panels

Of the roofs being replaced in this stage of the project, none are ideally suited for PV panels as only a small area of one faces south. There is, however, far more potential for a later stage of the project when replacing the Nave roof, half of which is south facing. If a system were to be introduced at this stage it would need to have the ability to capture the energy created for later use in the building. Purely feeding into the National Grid does not reduce the Cathedral carbon footprint but merely offsets it. Storing energy would require batteries, which have the same visual intrusion problems as air-source heat pumps but could potentially be hidden. The more pertinent drawback is the difficulties of obtaining planning consent for the addition of PV panels to the roofs, especially since such demands are being placed on us over the material of those roofs. Some Cathedrals in England have managed to obtain consent for PV panels but only on shallow-pitched roofs behind parapets that cannot be seen from the ground (in the image above, clockwise from top-left: Chester Cathedral; Gloucester Cathedral; Portsmouth Cathedral; and King’s College, Cambridge). Such concealment is impossible to achieve at the Cathedral. Whilst it may be that planning considerations change in the future, for the present phase, current policy would prevent the incorporation of a PV system on the roof. If this changes by the time we reroof the nave, PV panels are a solution we would absolutely support.